Is The Book of Moses From the Brass Plates?

I recently had a discussion with Latter-day Saint scholar Jeff Lindsay. Among other topics, we discussed the origin of the Book of Moses and why it contains numerous phrases and references found in the Book of Mormon. Here is what he had to say:

“A few years back, I was drafting a rebuttal to a piece by a self-described Latter-day Saint—what some might label a "cultural Mormon." His approach was typical: downplay the scriptures, discredit the Book of Mormon, reduce Joseph Smith to a clever fabricator. His claim? That the Book of Mormon couldn’t possibly be true because it references the Exodus—specifically 1 Nephi 4:2, where Nephi tells his brothers to be "strong like unto Moses." This critic argued the Exodus narrative was a post-exilic invention, conjured by later Jewish scribes under Persian influence to backfill a national myth.

I took issue with that—strongly. Yes, some scholars dismiss the Exodus. But others—serious, credentialed scholars—make a robust case for its historical core. Linguistic, cultural, and geographical markers trace back to ancient Egypt. But here’s where things get fascinating: I began to re-examine 1 Nephi 4:2, and something about it stood out. Nephi says, “Be strong like Moses.” But the biblical Moses isn’t typically described as “strong.” Quite the opposite—when Israel faced Amalek, he needed help holding up his staff. The word strong is used for Pharaoh, for prophets, for the Lord Himself—but not for Moses.

So why does Nephi use that word?

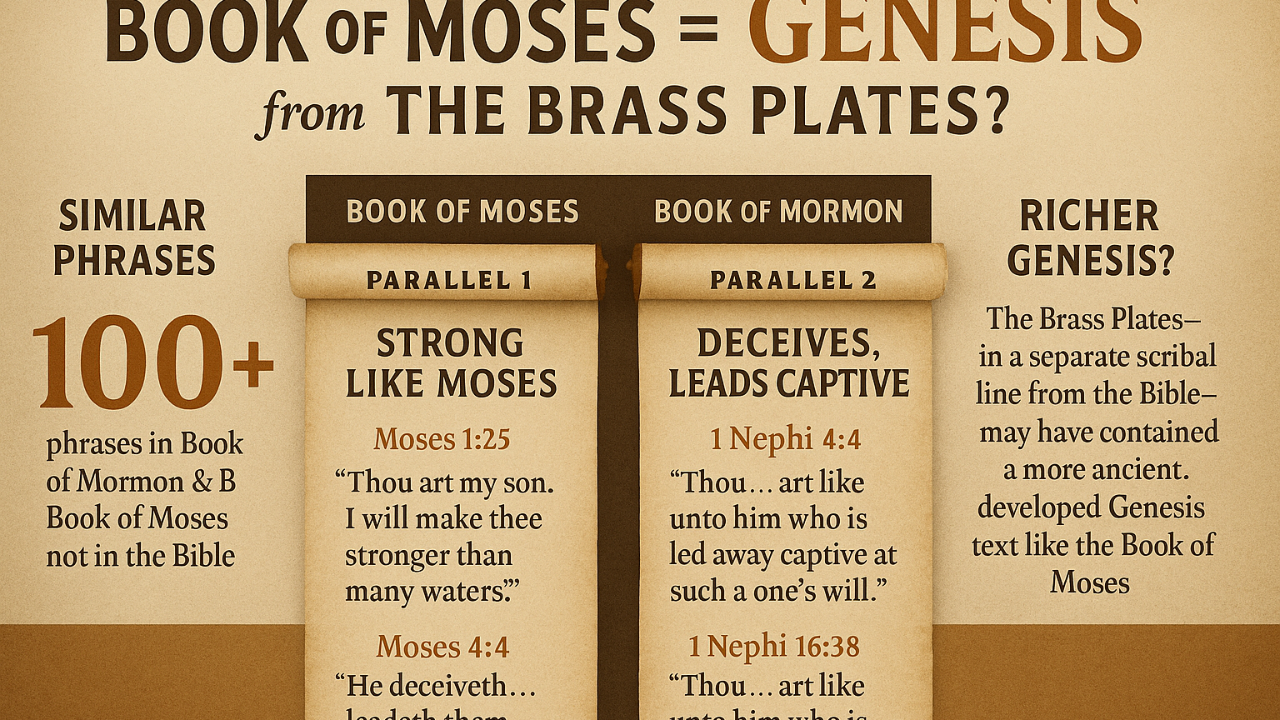

Shortly after that question surfaced, I came across a pivotal article by Noel Reynolds titled “The Brass Plates Version of Genesis.” Originally hard to find, it’s now published in the Interpreter. In this article, Reynolds compares the Book of Moses to the Book of Mormon and uncovers a startling pattern: dozens of words and phrases that don’t appear in the Bible—but appear in both the Book of Moses and the Book of Mormon. Not just once or twice. Over and over. The influence, interestingly, doesn’t go from Book of Mormon to Moses—it goes the other way. That shouldn’t be possible if Joseph Smith wrote the Book of Mormon first.

Here’s one compelling example: in 1 Nephi 16:38, Laman accuses Nephi of being a deceiver who wants to lead them into captivity. That’s standard sibling rivalry until you read Moses 4:4, which describes Satan in strikingly similar terms: one who "deceives," "blinds," and "leads captive at his will." It’s not just an echo—it’s a deliberate parallel. Laman is accusing Nephi of being satanic. And Nephi writes it down. Yet Moses 4:4 wasn’t translated until after the Book of Mormon was published. That’s not an accident. That’s intertextuality—and it runs deep.

Reynolds originally documented 33 parallels. When I came across 1 Nephi 4:2 and thought of Moses being made “strong,” I wondered—could Nephi have been quoting something on the brass plates? When I opened Moses 1, there it was: in verse 25, the Lord tells Moses, “I will make thee stronger than many waters.” That’s it. That’s the backstory Nephi knew—and we only got it years later.

We’re now up to 146 clear intertextual connections between the Book of Moses and the Book of Mormon. Not all equally strong—but many compelling. And they don’t appear at random. Nephi—who had the brass plates—uses them most. His sermons, visions, and language are saturated with Book of Moses themes. His brother Jacob follows closely behind. Lehi, especially in 2 Nephi 1, is firing off one allusion after another.

But once you leave that inner circle—once you move into the record of Zeniff—there’s silence. Until Abinadi picks up the thread, quoting Isaiah and preaching Christ, and then Alma takes it further. Alma’s sermons are thick with brass plates language—he was a student of the scriptures. Omni? Almost nothing. Even Mormon, who abridged the record, shows fewer references than Nephi or Alma. The pattern fits the timeline. Those who had access to the brass plates quote from them. Those who didn’t, don’t. That’s not random. That’s structure. That’s real.

This insight dovetails with Reynolds’ other work—tracing the scribal traditions of Judah and Manasseh. What we’re seeing in the Book of Mormon is not just a different volume of scripture. It’s a different tradition. A Josephite tradition. The Book of Moses, with its language, themes, and names like the Lamb of God, seems to come from that Manassite line—where Christ is not just implied but named, worshiped, and revealed.

Take Moses 7:47, for example: Enoch weeps over the Lamb slain before the foundation of the world. That’s not your standard Judahite language. That’s temple-centered, revelatory, and apocalyptic—much like what Nephi sees in 1 Nephi 11. There, the Lamb of God is shown to Nephi, along with the future of his people, the Gentiles, and the promised land. But the vision stops. The angel says, “You can’t write the rest. That will come from my servant John.” And what does John give us in Revelation? The Lamb. It’s one long prophetic arc—from Enoch to Nephi to John. And it all centers on the Lamb.

This matters. It matters because it means the Book of Mormon isn’t borrowing from the Bible—it’s drawing from an ancient, sacred reservoir of revealed knowledge. And the Book of Moses isn’t a late invention—it’s part of that same stream. Together, they form a revelatory echo chamber—one that testifies of Christ, of covenants, of cosmic opposition, and divine strength.

When I step back and look at this—when I consider that Joseph dictated the Book of Mormon in 1829, and then translated the Book of Moses a year later—it’s astonishing. There are detailed connections, literary and theological symmetry, and narrative consistency that span both books. These aren't coincidences. They’re fingerprints. Divine ones.

It’s one of the clearest and most powerful evidences for the authenticity and divinity of both texts.”

I believe that the Book of Moses is, or comes from, the Genesis of the Brass Plates. We need to know that the Brass Plates are NOT the Old Testament. While they share numerous books, they likely come from a different traditions, peoples (the Brass Plates come from Josephites and the Old Testament comes from Judah) and scribal schools. The Brass Plates are also the source scripture for the prophets of the Book of Mormon. We might think of the Brass Plates as part of the “Stick of Joseph.”

Greg Matsen